Executive Summary

TikTok is one of the fastest growing social media platforms in the world, claiming 1 billion monthly users. 11 million of those users are German, according to TikTok. The platform played a crucial role during the 2021 German Federal election campaign, as our recent research has shown. On September 26, 3 million first-time voters turned up at the polls, and now some observers are pointing to TikTok as a possible explanation for the turnout among young voters.

In addition to the qualitative research on TikTok we conducted, we also tested out quantitative approaches to studying TikTok. During the period July-Oct 2021, we worked with the Algorithmic Transparency Institute (ATI) and Bayerischer Rundfunk (BR)’s data team to comb through 366,062 unique TikTok videos that had been collected using Junkipedia, an investigative tool run by ATI. Junkipedia is described by its creators as “a technology platform that enables manual and automated collection of data from across the spectrum of digital communication platforms including open social media...powered by the active engagement of a large and diverse network of civic-minded stakeholders.”

In this report, we explain how the experiment was designed and what we observed on TikTok during the German election. In reflecting on our experience investigating the platform, we believe it demonstrates the need for better transparency tools for platform research.

Currently, there are major hurdles to conducting research about TikTok. Unlike its peers Google, Facebook, and Snapchat, TikTok has not yet created tools like an API or an ad archive to enable journalists or civic researchers to access platform data. Without such tools, it is nearly impossible for us to look “under the hood” of the TikTok algorithm and identify patterns of abuse or harm. We urge TikTok to develop meaningful transparency tools and archives to empower civil society oversight.

Introduction

“For everyone who has been on Tiktok for the last two years and has seen what young people are talking about, this should come as no surprise,” tweeted German journalist and TikToker Victoria Reichelt.

One day after the official results of the German Federal Election 2021 were announced, the German public was already embroiled in a discussion about the outcome of the election. The turnout from voters under the age of 25 came as a surprise to many election observers: Rather than sticking with the two former Volksparteien (people’s parties) CDU/CSU and SPD, the nearly 3 million first voters mainly opted for the Free Democratic Party (FDP, 23%) and Alliance 90/The Greens (Bündnis 90/Die Grünen, 23%).

While the reasons for young people turning up to vote can’t be directly attributed to TikTok or any other social media platform, TikTok’s influence in Germany suggests that it may have played a crucial role during the election season. Our own research published in Sept 2021 on the German election raised concerns about the lack of scrutiny TikTok receives relative to the size of its user base, user engagement, and overall revenue.

In this follow-up report, we summarize what Mozilla, journalists, and other civil society organizations observed on TikTok ahead of the election. We also lay out the methodological approach we used to sort through TikTok data collected by ATI. Finally, we reflect on some of the challenges that prevent researchers from conducting large-scale research of this kind, and make recommendations to TikTok for empowering civil society researchers to study the platform.

Investigating the election on TikTok: Dirt and disinformation

Recent investigations suggest that people have been using TikTok to try to influence public opinion around the German Federal Election. The Institute for Strategic Dialogue (ISD) published a report showing how not-marked election ads, negative campaigning, and hate speech and extremism were spread on the platform. To achieve the goal, people used a number of tactics, utilizing fake accounts, TikTok aesthetics, underage influencers, and platform-specific memes and sounds.

In our past research, we uncovered several TikTok accounts impersonating prominent German political institutions and figures, using the handles @derbundestag and @frank.walter.steinmeier. These accounts are in clear violation of TikTok’s community guidelines, which prohibit impersonating someone else or misleading users about an account’s identity or purpose. Despite the fact that these two accounts attracted thousands of followers and likes for months, they were taken down by TikTok only weeks before the election.

In addition, the journalists at Bayerischer Rundfunk discovered a viral election-related TikTok video spreading misinformation about Alliance 90/The Greens, using the 1990s rap song “Gangsta's Paradise.” The sound was used by more than 40 creators to produce similar videos, some of them gaining more than 1.8 million views. The plot and the setting of the video is always the same: It is election night, the Greens have won, and they’re presenting new rules for life in Germany. Concerningly, 6 out of 7 statements in the video have been debunked as false claims by independent fact checkers. Such videos may fall under TikTok’s rules banning misinformation, but the problem was not addressed by the platform.

There are limitations to conducting large-scale, quantitative research into TikTok. Because the platform does not currently provide any comprehensive transparency tools or an API, researchers must develop new methodologies and technical infrastructure in order to identify patterns of harm or abuse. Mozilla’s past research in the US, for instance, involved a mix of manually looking through relevant hashtags, accounts, and videos and querying an unofficial API to uncover issues on the platform. The researchers at ISD built a dataset of 1,030 TikTok videos as part of their research into hate speech and extremism on the platform. The WSJ’s video investigation was based on a large dataset of TikTok videos using 100 automated accounts.

There is an urgent need for better tools to do large-scale research on TikTok. Despite some hints dropped by TikTok, the operating principle of the platform remains a black box, leaving external researchers locked out – unless they can find ways to circumvent the missing API.

Emergent approaches to large-scale TikTok research

Our report on TikTok and the German election was rooted in qualitative observations and methods: reviewing TikTok’s policy materials, searches for hashtags and accounts, analyzing videos and labels, and stakeholder interviews.

We have also been experimenting with quantitative approaches to studying TikTok at a larger scale. We reviewed a large dataset of over 366,000 German TikTok videos methodically collected by Algorithmic Transparency Institute’s investigative tool Junkipedia. ATI is a program of the National Conference on Citizenship (NCoC), a non-partisan non-profit dedicated to strengthening civic life in the US. ATI’s goal: to bring greater transparency to the digital platforms that impact civic discourse.

Junkipedia is described as “a technology platform that enables manual and automated collection of data from across the spectrum of digital communication platforms including open social media” to empower civic-minded platform research. Junkipedia is currently used by public interest researchers, journalists, and advocates to study how misinformation, political speech, hate speech, and other forms of sensitive or harmful content are amplified online by social media algorithms.

From July 5 - Oct 4 2021, we partnered with data journalists at Bayerischer Rundfunk (BR) and ATI to categorize, tag, and analyze the hundreds of thousands of videos in the dataset. The shared goals of Mozilla, ATI and BR were: (1) to establish a methodology for studying political speech on TikTok; and (2) to build a technical infrastructure to collect data surfaced by TikTok’s recommendation algorithm, known as the For You Page.

The Junkipedia platform operates as follows: First, publicly available TikTok posts enter the system via automated collection from APIs, user submissions from tiplines, and synthetic accounts. The synthetic accounts, created by ATI specifically for the purpose of this project, were designed to emulate the behaviors of users across the German political spectrum. Next, researchers view, categorize, and tag the TikTok posts within Junkipedia. They can monitor lists of channels and search queries to look for content that matches their investigative criteria or research questions, and then organize, annotate, analyze, and export that data.

A researcher view of TikTok posts in the Junkipedia platform.

The project went live with test data collection on July 5th, 2021. Large scale data collection was initiated in August, and continued through the first half of October. During this entire project, 366,062 unique TikTok videos were collected using 69 synthetic accounts in total. Alongside the WSJ’s TikTok investigation, which collected data using 100 synthetic accounts, this is one of the largest TikTok datasets researchers have been able to work with.

ATI collected hundreds of thousands TikTok posts, including nearly 10,000 posts that TikTok itself marked as related to elections. It would be nearly impossible to amass and identify this volume of content using manual methods. Ideally, this methodological approach would allow one to make stronger claims about patterns and trends we are seeing, because the data sample is more representative. For instance, it would be difficult to make a generalizable claim such as “X% of the engagement on political TikTok posts appears to be positively engaged with ‘Y-party’ content,” using only anecdotal data.

In the following sections, we’ll give an overview of the research methodology and reflect on what we learned during this experiment. This will include descriptions of data segments and the synthetic agents, data sorting and labeling, initial finding, and our challenges and learnings throughout the process.

Creating the Segments and Synthetic Agents

“We established the project with the premise that there are different types of real human users on TikTok, and we wanted to emulate certain characteristics of those users,” explains Cameron Hickey, Director of the Algorithmic Transparency Institute.

For example, there are some users interested in makeup tutorials, others interested in dance memes, and others interested in crafting. There are also users who are interested in political content – typically content that aligns with their own perspective. Various “segments” were created to represent a wide variety of political viewpoints in Germany.

First, researchers designed various segments intended to represent viewpoints from each political party in Germany. They also created segments designed to represent broader political viewpoints and issues, including segments labeled “anti-mainstream,” “climate protection,” “general politics,” and “non-political,” a category which acts somewhat like a control group for this experiment.

Various segments created to represent the German political landscape.

For each segment, ATI created multiple synthetic accounts programmed to engage on TikTok according to the criteria defined for them. These accounts only engaged in passive behaviors: following accounts, watching videos, and rewatching videos. The accounts did not engage in active behaviors, such as liking or commenting on a video.

Synthetic accounts engage with the set of coded accounts, via only passive actions.

The system works as follows: There is a client and a server. The client runs on a mobile app, and performs various actions of a user on TikTok. The client requests tasks from the server such as “follow this account,” “watch this video,” or “scan your feed for 30 minutes” as well as “rewatch any videos from ‘X account’” or “rewatch any videos using ‘Y term’ in the caption.” The client proceeds to run TikTok, analyze what videos it is watching, and then make a decision to rewatch or skip each video. Every video the client encounters is sent back to the server and is registered as an “observation.”

Posts are collected from the FYP feed of the synthetic accounts.

Several challenges occurred when ATI was collecting data from TikTok, including both the underlying difficulty of collecting data from a native mobile app, and the specific challenges posed by anti-scraping measures implemented by TikTok. “Automating the process is a continuous cat-and-mouse game with the platform and the technology,” says Hickey. “TikTok is very well designed to make creating synthetic accounts difficult, and so this process remains entirely manual.”

This is to be expected: After all, TikTok’s Terms and Conditions prohibit the use of automated scripts to interact with TikTok in order to prevent abuse of the platform. TikTok is a public platform like Twitter or YouTube, so all the posts ATI collected are already publicly available and anyone can see them online. However, TikTok has not yet created tools like an API to enable researchers or developers to access platform data, and so very few options exist for public interest researchers seeking to perform large-scale, quantitative research about the platform. We raised concerns with TikTok’s complete lack of transparency in our previous report. This is an issue Mozilla has spoken about frequently, and we are committed to improving the landscape of public interest research.

Throughout the research design process, ATI took a number of steps to protect user privacy. First, the system only collected TikTok content that was already publicly available. No personally identifiable information was collected and no comments on videos were collected. Second, the data is being stored for exactly two (2) years after it was collected, at which point it will be deleted. Finally, the code is being continuously monitored and regularly updated by ATI to match the latest TikTok UI, to avoid any unintentional data collection. More information about Junkipedia’s research and data privacy practices appears on its website and Terms of Service.

Sorting and Labeling the Data

As the data flowed into the Junkipedia platform, we worked together with BR journalists and ATI researchers to sort through a huge number of videos to determine whether or not they were relevant to the research. To give you a sense of scale: Each day of the experiment, roughly 3000 - 9000 TikTok posts were collected in the Junkipedia platform. The majority of posts had to be labeled manually by researchers.

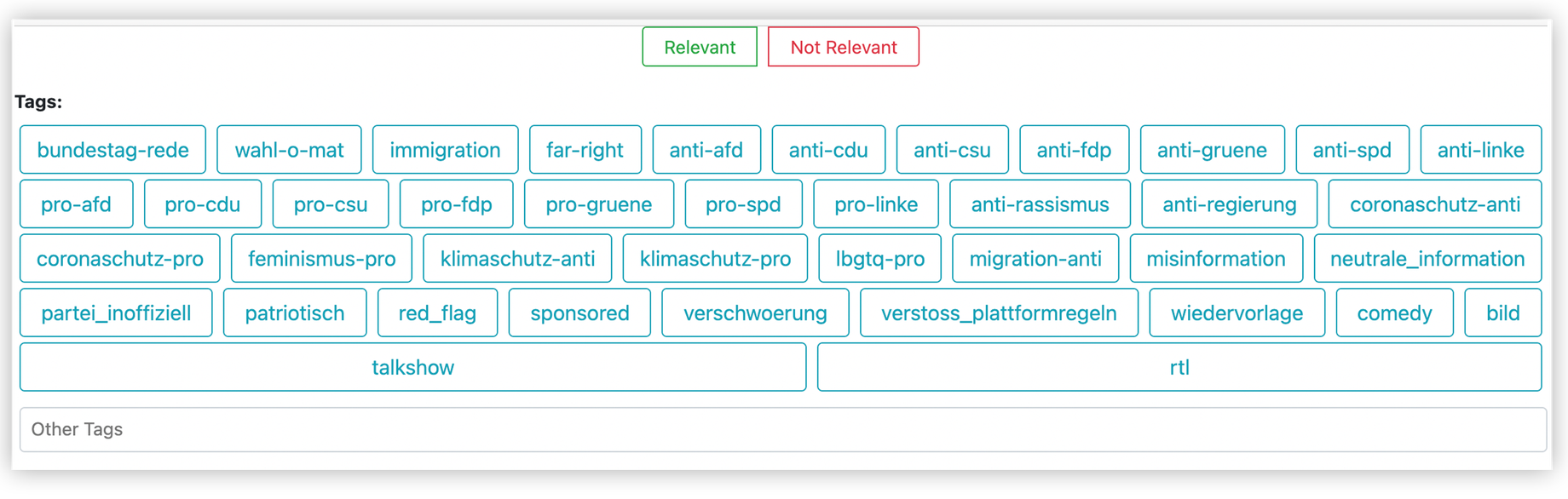

We divided the task into two steps: First, an initial screening determined whether the post was “relevant” or “not relevant” to our investigation. Then, in a second screening researchers applied specific tags or labels to each video to enable further analysis. Those tags included things like “anti-migration,” “pro-feminism,” “anti-spd,” and “misinformation.” We produced this list of labels prior to data collection, but new labels were created during the process as needed.

A researcher view of tagging individual posts in the Junkipedia platform.

In the end, a total of 366,062 unique TikTok videos were collected in the Junkipedia database between July 5 and October 4. So far, more than 34,000 of those videos have been labeled as relevant/not relevant, with roughly 250 videos assigned additional tags. Significant labor and time would be required to complete a full analysis.

Initial Findings

We used the data gathered by the platform as a tool for surfacing TikTok videos and accounts relevant to our research questions. Building off findings from our Sept 2021 report, we identified more accounts impersonating German politicians and observed further proof that TikTok’s automated election banners are not working properly.

Amplified Fake Accounts

Our first report found that accounts impersonating German political figures were thriving on the platform. In addition to the two fake accounts we identified in September, we used Junkipedia data to uncover more accounts impersonating German politicians on TikTok. For instance, ATI’s synthetic accounts alerted us to the existence of an account @_angela_dorothea_merkel, impersonating the German chancellor Dr. Angela Merkel. We first learned about the account when we had noticed that several of the synthetic accounts ATI had programmed – bots from segments labeled “Anti-Mainstream,” “CDU/CSU,” and “AFD” – had been served the videos on their For You Page feed. They watched the videos on August 17, September 11, September 14, and September 15, respectively.

While we know the account was deleted or removed sometime after September 15, by that point its videos had been viewed several million times by TikTok users, according to the snapshot we saw in Junkipedia. It’s difficult to know how far the account’s messages reached and whether or not its videos influenced German voters. TikTok’s Community Guidelines prohibit posing as another person or entity in a deceptive manner, and yet the account remained up for months during the lead-up to the election.

Automated Labeling

Starting July 20, various TikTok videos were labeled with an informational banner at the bottom that stated “Erhalte Infos über die Bundestagswahl in Deutschland“ (“Get info on the German federal election”), with a link to an information page about the German election.

In our previous research, we determined that TikTok’s automated approach to labeling content about the German election was not working effectively, with videos being improperly labeled. We concluded that a fully automated approach relying on keywords weakens the intended goal of the labels, and may even damage efforts to sensitize users and/or redirect them to verifiable, trusted sources of information.

Building on that research, we are analyzing 10,000 videos in the Junkipedia database that received the automated banners to determine what factors were used to apply the election label. We suspect the system is based on a crude list of hashtags that relate to the German election. We saw, for example, every post that used the tag “#merkel” received the label, but posts that included the word “merkel” without the hashtag did not. If this is true, that means that anyone who wanted to circumvent the automated banners simply had to leave out the “#” from their caption.

Challenges and Learnings

Pulling off a large-scale research project like this one is difficult. Although it’s too early to draw quantitative insights from the data, we can still reflect on what was successful and what was unsuccessful about the experimental research design. Based on what they learned, ATI researchers are already working on adapting the system to operate more efficiently at scale to enable future research projects and investigations on TikTok.

Distinct Segments

The biggest challenge is that it’s nearly impossible to create customized segments that accurately represent the different ideologies distinctly. “We were highly successful in training the recommendation algorithm to feed our agents videos that were about politics and the election, as opposed to influencer memes, or video games content,” says Hickey. “However, at this point, it does not appear we were particularly successful in generating a truly distinct “CDU” or “AfD” recommendation feed. This likely has to do with the small overall volume of political posts on TikTok and the fact that we tried to do this for six distinct parties who have overlapping political interests. In a different context, such as the US two-party system, it could be much more effective based on the learnings.”

So far, the videos observed by segments in their For You Page don’t seem to be different from the videos observed by other segments. But it’s still early in the experiment and over time that’s likely to change, as agents spend more time watching videos on the platform and their feeds become more personalized. “A qualitative analysis did not reveal distinct feeds for the segments, however a comprehensive quantitative analysis is currently underway to determine how unique each feed was depending on the rules followed,” says Hickey.

Simulating User Behavior

Despite best efforts, it is very difficult for ATI to simulate real user behavior on the app using automated methods. Real people have complex, varying interests; they are interested in lots of things besides politics. In addition, real people don’t decide what videos to watch just based on the caption. Right now, the agents can’t make decisions based on the content of the video – music, text, speech, or imagery – which is how a real person would decide to watch or skip a video.

Another challenge is that the synthetic agents are not yet autonomous. Currently, the agent is programmed to scan TikTok and follow simple rules like “rewatch any video that contains the terms “covid,” “vaccine,” or “pandemic.” The agent is also capable of opening and watching a list of videos, following a list of accounts, and scanning its For You Page and rewatching videos from specific accounts or videos that contain specific terms in the caption. However, right now agents can’t make decisions about what to rewatch based on the content of the video. The system will require further development before agents can perform such behaviors.

Detection of Agents

Another question arose during the experiment: Could TikTok’s automated system for detecting bots be interfering with the outcomes of the experiment? TikTok’s 2020 Transparency Report reported on how many inauthentic accounts were removed in 2020, so we know the platform has technical tools in place to identify inauthentic behavior. Throughout the experiment, ATI observed and ran into aspects of TikTok’s automated system for identifying inauthentic activity, but so far the agents have been operating as planned without issues. However, it’s difficult to know to what degree TikTok detected the agents and is taking steps to limit their engagement.

Recommendations

As we’ve shown in this report, researchers and journalists seeking to study the TikTok platform will run into lots of challenges. TikTok currently does not provide any transparency tools or APIs to researchers seeking to study the platform. Without such tools, it is nearly impossible for researchers to look “under the hood” of the TikTok algorithm and identify patterns of abuse or harm. We therefore urge TikTok to develop meaningful transparency tools and archives to empower civil society oversight.

Specifically, TikTok should release tools to empower public interest researchers and journalists to study the TikTok algorithm. That could include a public API researchers can query, a tool that simulates how the FYP feed works, or comprehensive transparency reports and archives. For instance, Twitter has a publicly available API and recently released a version of the API for academic researchers that features more precise filtering options.

In addition, TikTok should develop a publicly-accessible library or repository of all ads, branded content, and promotions running on the platform, as other platforms have done to varying degrees (see: Facebook Ad Library, Snap Political Ad Library, Google Transparency Report). TikTok should follow Mozilla’s guidelines when designing this repository and ensure that it includes content from all advertisements running on the platform, including paid partnerships. This will enable community oversight of TikTok’s policy enforcement and support independent research into the online advertising ecosystem.

Conclusion

With an ever-growing user base and skyrocketing revenue, TikTok is on course to define the next era of social media. And yet our research demonstrates that there is a major transparency gap on TikTok. With the platform increasingly falling behind its peers, we urge TikTok to develop meaningful transparency tools like an API or an ad archive to empower civil society oversight of the platform.

References

Behme, Pia. “Ziel ist der Vertrauensverlust in das demokratische System,” DLF, 24 September 2021, https://www.deutschlandfunk.de/desinformation-im-bundestagswahlkampf-ziel-ist-der.1773.de.html?dram:article_id=503439. Accessed 9 October 2021.

Hegemann, Lisa. “Was hängen bleibt. Desinformation im Wahlkampf,” Zeit.de, 29 September 2021, https://www.zeit.de/digital/internet/2021-09/desinformation-wahlkampf-bundestagswahl-2021-annalena-baerbock-gruene/. Accessed 9 October 2021.

“Inside TikTok’s Algorithm: A WSJ Video Investigation,” The Wall Street Journal, 21 July 2021, https://www.wsj.com/articles/tiktok-algorithm-video-investigation-11626877477. Accessed 9 October 2021.

Köver, Chris. “Warum die FDP bei Erstwähler*innen punktete,” Netzpolitik, 29 September 2021, https://netzpolitik.org/2021/bundestagswahl-warum-die-fdp-bei-erstwaehlerinnen-punktete/. Accessed 9 October 2021.

Schiffer, Christian. “FDP-Erfolg bei Erstwählern: Die TikTok-Partei,” BR24, 27 September 2021, https://www.br.de/nachrichten/netzwelt/fdp-erfolg-bei-erstwaehlern-die-tiktok-partei,SkD28Sg. Accessed 9 October 2021.

Schmid, Mirko. “Desinformationen vor der Bundestagswahl 2021: Baerbock Ziel Nummer eins,” Frankfurter Rundschau, 6 September 2021, https://www.fr.de/politik/bundestagswahl-2021-baerbock-laschet-desinformationen-luegen-manipulation-gruene-cdu-afd-90965040.html. Accessed 9 October 2021.

Schöffel, Robert; Khamis, Sammy. “Videos bei TikTok: Falschmeldungen und ihre Verbreitung,” BR24, 16 September 2021, https://www.br.de/nachrichten/netzwelt/videos-bei-tiktok-falschmeldungen-und-ihre-verbreitung,Sj6kb1H. Accessed 9 October 2021.

Seeburg, Carina; Wermter, Jonah. “Wahlkampf auf der Blödelplattform,” Süddeutsche Zeitung, 25 September 2021, https://www.sueddeutsche.de/politik/bundestagswahl-tiktok-soziale-medien-fake-news-politik-1.5420761. Accessed 9 October 2021.

Sudah, David-Wilp; Levine, David. “Im Visier der Manipulatoren,” Tagesspiegel, 2 September 2021, https://www.tagesspiegel.de/politik/negative-campaigning-im-visier-der-manipulatoren/27575044.html. Accessed 9 October 2021.